!!! My website has

moved: please update your bookmarks to debunix.net !!!

Live food

cultures II

I have acquired quite a few different cultures gradually,

and some

work well for me and some don't. These are the ones I have kept going,

some better than others. My favorites are the BBS, microworms,

and grindals, because these are easiest for me, and I feed them to my

fish daily. In order of size, smallest to largest, they are:

Vinegar Eels

Microworms

Baby Brine Shrimp

Grindal worms

Grindal worms on green scrub pads

Daphnia

Daphnia vs Moina

Confused flour

beetles

White worms

Livebearer fry

Red Wigglers

Snails

I discuss my experiences with each below, and I've included some

more web resources here. I

also have some notes from fellow MASI and SLAKA member Jack Heller, a

master breeder of killifish, on how he does some of his live food

cultures, including paramecia, white worms, and fruit flies, here.

And I continue to envy Charles Harrison's cool basement that

allows him to keep thriving cultures of white worms year round--see his

setup for those here.

For truly in depth information on culturing these and many other live

foods, there is now a terrific, up-to-date resource by my friend Mike

Hellweg, a master fish breeder and fish keeper who has just written a book on the subject. You can reach him here to find out how to get a copy of his Culturing Live Foods.

I've learned a bunch from my copy already, and am going to change

some of my formulas to reflect this new information. He discusses

all of the foods I have here in more depth, plus many smaller, larger,

and some just plain finickier than I have been able to keep going.

This book is also a primer on spawning fish--just because the

discussion is framed as culturing them as feeders for other fish

doesn't mean the tips and strategies mentioned are any less applicable

to breeding a wide variety of desireable fish. That's a lot of

great info for one book.

Vinegar Eels

The newest addition to my collection of critter cultures, these are

supposed to be small enough for even tiny rainbowfish fry. You

can't really see the individual worms without magnification, but they

make the water cloudy when they're doing well. They also have the

advantage of swimming throughout the water column, which is important

for those small fry that live near the surface. But

although

these are supposed to be very

easy to keep--able to survive long

periods of neglect--but they can be killed. They are called

"vinegar" eels but they prefer a 1:1 dilution of vinegar (I use apple

cider vinegar and tap water). They do well with some peeled apple

slices (to avoid bad effects from any sprays on the skin of the apple,

which can kill them) or a teaspoon of applesauce in a pint of culture,

with a small spoonful of sugar stirred in. They're very easy to

keep alive, although they can be killed by (1) unpeeled apples (2)

drying up of the culture (3) mold on an overfed culture (and you can

probably find a few more if you're creative).

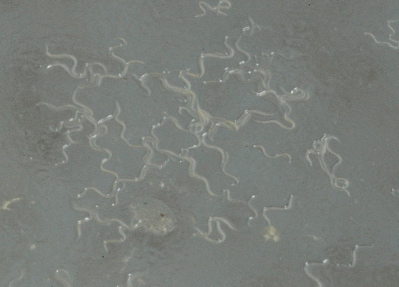

Though to the naked eye they appear mostly like specks of dust in the

liquid, up close they're proper worms indeed:

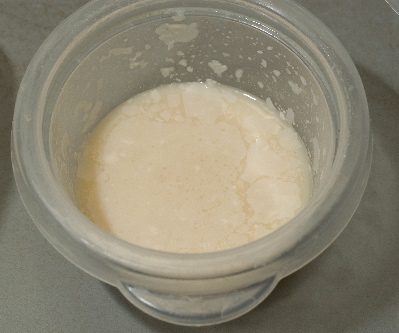

Here they are in their new culture with some fresh cut peeled apples:

And the apples will soon break down into mush like that on the bottom

of the jar. They will stay in this wide-mouthed jar, coverted

with a bit of fabric to keep out the fruit flies:

Jack Heller likes to harvest his by pouring them through a coffee

filter, flipping the filter over into a dish of water, so that the eels

fall into the water, and uses a dropper to feed them

to fry. Another technique is to use a long necked bottle, fill it

with the eel culture partway up the neck, then stuff in a piece of

filter floss, cover with water, and wait a few minutes for the eels to

migrate up into the water (this keeps vinegar out of the tank, but

avoids the need for filters). I will try out both harvest

techniques if I can get them established.

Fortunately, there seem to be plenty of infusoria in

my planted tanks to get the

littlest fish started just fine; I've even had a little pseudomugil

rainbowfish appear spontaneously in one of them.

Microworms and Walter worms

Update coming soon....after reading a very interesting

article about these in the Journal of the American Killifish

Association, I tried these on potato flakes for the first time a few

weeks ago, and they're doing great. I am quite impressed, and all

the new cultures I've started are now on potato flakes.

These are very small, but at 1-2 mm long, are visible as tiny threads

in the water when you feed them to your tanks. The fry of most

fish can take these soon after hatching: they're considerably

smaller in diameter than even newly hatched baby brine shrimp.

They do fall rather quickly to the bottom of the tank, though, so top

swimming fry may not get enough of them. I've had two different

varieties that are available locally, and now only keep so-called

"Walter worms". These are a type of microworm that spend more

time in the water column before they sink than do regular microworms

(click here to see an experimental

demonstration of the difference).

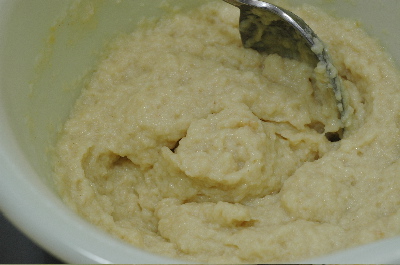

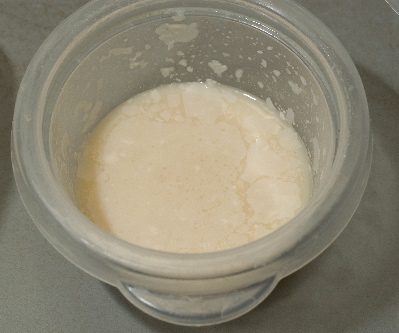

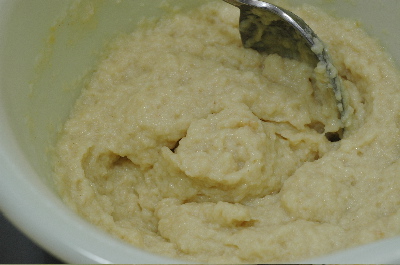

I cultivate these on a mix I learned from Al Andersen's

talk on live foods at the MASI show in 2003: gerber instant

oatmeal or mixed grain cereal plus a bit of brewers yeast plus a little

instant dried yeast (about a pinch of instant yeast plus a tablespoon

of brewers yeast to a cup of cereal). I think the worms are

supposed to eat the live (activated)

yeast, which feeds on the cereal and brewers' yeast. I make

this up in bulk and just add equal parts mix and

water to a clean dish, so that it is a thick paste like this:

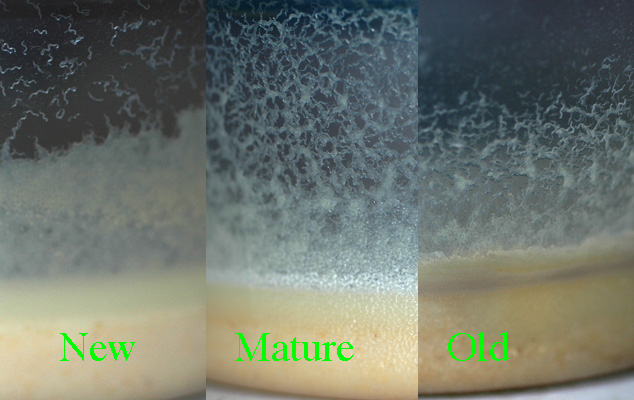

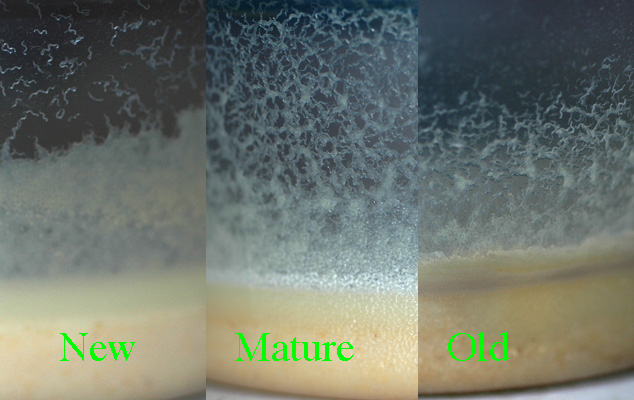

I place a dollop of this in a small plastic container, and add a few

drops of liquid from an earlier culture. As the culture matures,

it will get thinner and darker , and that is normal.

After

reading a very interesting

article about these in the Journal of the American Killifish

Association, I tried these on potato flakes for the first time a few

weeks ago, and they worked great, but the smell got nastier quickly, so

I have gone back to the baby cereal. I now do it simpler and add

the cereal mix to the container and water to that, without using an

intermediate step of mixing it up in bulk in the bowl.

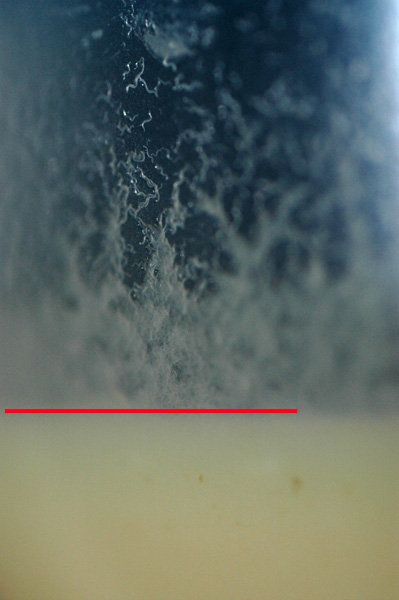

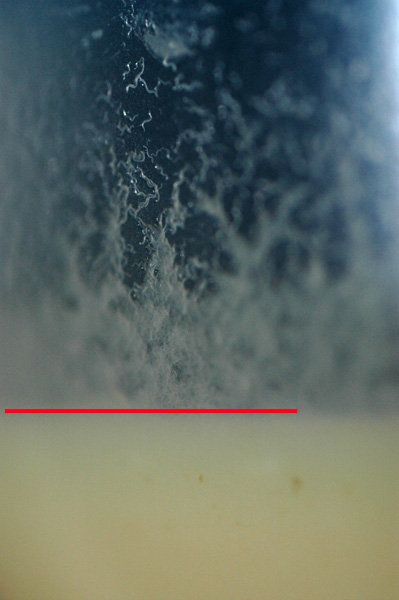

After about a few days to a week, the worms start crawling up the side

of the

containers. The cultures are harvested daily by wiping

the worms off the side of the container with a finger and kept going

until the yields

drop, usually for about 3 weeks. I looked through the cheap

disposable containers at the grocery store to find some that I could

stack in a small container, because the easily harvestable worms come

from the sides of the container, as here above

the red line:

where I rub them off daily with my finger to feed the fish (you can use

a rubber scraper or a popsicle stick for this part if you're squeamish,

or your hands are dirty):

There are more worms living in the lower part of the culture, but

harvesting them leads to putting a lot of cereal debris in my

tanks. So I prefer to use multiple small containers, here trying

to get the maximum amount of side-wall surface for harvesting.

Yogurt containers and margerine tubs are often used, but I found some

little disposable cups that fit stacked in a box so they're easy to

handle. I poke holes in the lid with a pushpin for air exchange,

but be sure the holes are small or fruit flies can find their way in

(very very messy). These worms do fine, by the way, whether they

are kept in a light or a dark place.

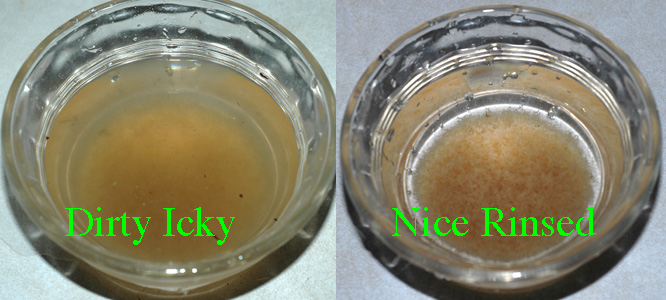

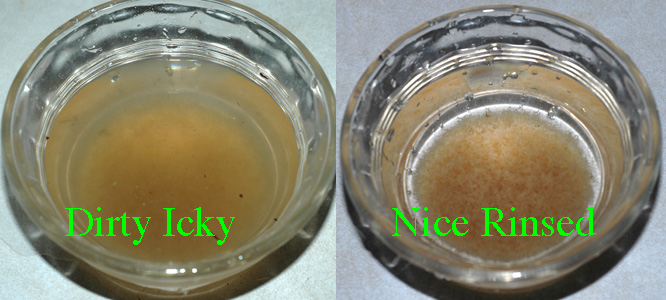

After swiping the wall of the container, I swirl my finger in a clean

cup of water. Then I rinse the worms through a brine shrimp next

to get rid of the cloudy cereal debris. I swirl

the containers daily to recoat the sides of the container after I take

off

the worms, which seems to encourage the worms to climb up the sides for

easy harvest. When the culture turns darker and fewer worms come

out, despite being stirred/swirled daily, I dump it and start a new

one, usually every 2-3 weeks. There are typically 2-3 fresh, 2-3

medium, and 2-3 older cultures going at any one time, and still I don't

get very many worms at once, but fortunately the little fish that need

these don't need a lot of them to grow .

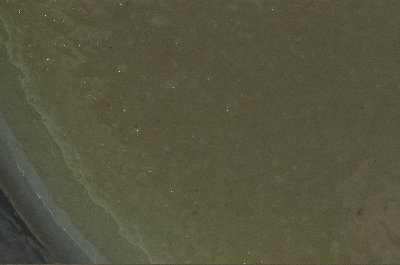

Sometimes a little skin of yeast or bacteria grows on top of the

culture, but does not harm the worms, and the flakes of it that end up

floating on top of the water are easily poured off before the worms are

poured into the net for rinsing:

If you don't see lots of worms on the side of the container, don't

despair. They're probably still in there. If you swirl the

culture and look at the surface closely, it should

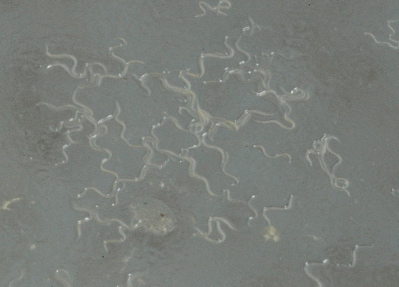

look like it is moving or bubbling, like this:

Looking a little closer up (this requires a magnifier) you start to see

the individual worms swimming at the surface:

And here they are climbing up the wall of the culture:

Jack noted that stirring some puffed rice cereal (not rice krispies,

but puffed rice) into an older microworm culture can keep it going for

weeks more.

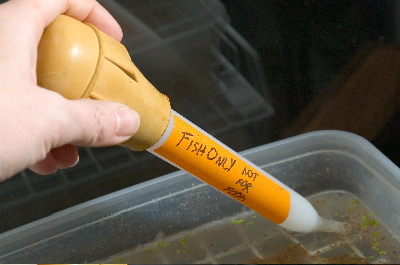

BBS

Newly hatched baby brine shrimp are a favorite not only of small fry,

but of most fish up to a couple of inches long. They're active

swimmers, dispersing throughout the water column, and survive for hours

after being added to a tank. I do these differently than most,

because I don't use air pumps at all

in my fishroom (which is my living room, and the live food area is my

kitchen too). I hate the noise they make (yes, I know the new

linear piston pumps are very very quiet, but even so....).

I hatch brine shrimp eggs daily in a 2 liter flask, set on a magnetic

stirplate. Each night I add 1L of room-temperature tapwater to

the flask and 1/2-1 tsp brine shrimp eggs (depending on how many small

fish there are to feed). 2-3 drops of bleach may be added per

liter to prevent the growth of unpleasant bacteria,

and since bleach is used to dechorionate the eggs to increase hatching,

I suspect it may help hatch rates used like this as well. The

flask is set to stirring overnight

on medium speed, enough to see a little whirlpool vortex in the middle

of the liquid. Stirring needs to be fairly vigorous for

good aeration.

The next morning I add about 1 1/4 ounces of

pickling salt. I keep the salt in a jar next to the stirplate and

flask, and keep a scoop in it that is just the right capacity.

It's all about making it easy to remember even when I am sleepy stupid

in the morning.

Some people think the type of salt makes a difference: most use

non-iodized salt, some people like rock salt or road salt, and Jack

Heller even adds a bit of epsom salts to his along with the rock

salt. I use the pickling salt because the three-pound box is a

convenient size for me to store.

At night I pour the contents into a 1 liter fat-separator measuring cup

(the spout comes

off the bottom) and leave it sit for a few minutes while I harvest the

microworms and feed the grindals.

http://debunix.net/fish/CharlesLiveFoodCulture.html#CharlesShrimpHatchery

http://debunix.net/fish/CharlesLiveFoodCulture.html#CharlesShrimpHatchery

Then I pour off the hatched

BBS from the bottom and leave the top-floating unhatched and empty

shells

in the separator. And I set up a new flask for the next night's

BBS. I use two flasks in rotation to let one dry while the other

is in use, and this keeps down the smell. When they get a nasty

film on the sides, a dilute bleach solution and rub with a bottle

scrubber will clear it right up.

I don't know what my hatch percentage is, but I get reliable

BBS production on a 24hr rotation and that works for me and my

fish. I may also be feeding some bad eggs, that hydrate but don't

hatch, and sink; this reportedly can make fish sick. I haven't

noticed any problems with my fish. Overfeeding BBS encourages the

proliferation of hydra. This has given rise to the idea that

hydra actually exist in the cans of brine eggs, and hatch out with

them, but to the best of my knowledge and that of my sources this is

not the case. The hydra may come along with live plants or fish

or gravel, and the BBS are a terrific food for them, so overfeeding

encourages the proliferation of hydra that were already in your

tanks. BTW, a bit of fluke tabs quickly takes care of the hydra,

so they don't harass or kill your small fry that are supposed to be

eating the BBS.

More common setups to hatch BBS are designed to use airstones for

vigorous aeration, and are setup so you can

turn the air off, let the hatched nauplii settle to the bottom of the

culture, then pour off directly from the bottom, or use a baster to

suck them up without bringing along the empty floaters. They are

also drawn to light, so a setup incorporating a light at the bottom

will help separate them from their shells. I used to keep a light

on over the culture 24/7, but have since discovered no change in the

hatching rates without it. I have some pictures of Charles

Harrison's brine shrimp hatchery here.

Grindal

Worms

I love the grindals because they like normal room

temperatures, unlike white worms that need it cool (I hate the idea of

running even a small refrigerator just to keep it cool for the worms to

feed the fish). I

grow them in small plastic boxes, as shallow as I can get (you're

really growing them only on the top surface, so deeper boxes just take

up more

room without providing more worms). I have a small rack

(purchased with some little "drawers" from an office supply store,

drawers discarded, that allows me to stack several in a small space)

that holds several of them under the sink (they prefer the dark), and

can stack more on top as

needed, giving me enough growing surface to produce more grindals than

all my fish can eat.

Each box is filled with half an inch to an inch of Magic Worm Bedding (Magic Products Inc),

kept quite moist. I use this bedding for my worm compost bin,

because it seems to keep the redworms happier, so I always have it on

hand. Other people use various soil or peat mixes, or go dirtless

with sponges or green plastic scrubbies. I trim the lids of the

boxes off on two sides

so they fit inset into the box, on top of the worms and their food, but

cover most of the box. The more of the surface you cover with the

lid, the more of it you can actively use for harvest. The edges

of the lid that remain provide a convenient handle, and the plastic lid is

easier and safer than the piece of glass that is often recommended:

The boxes are loosely wrapped in a plastic bag to keep out fruit flies

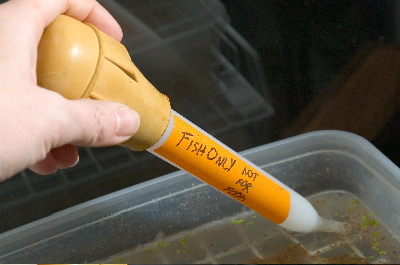

Each evening I take off the lid,

return any visible pellets of catfood (like this in the middle of this

closeup) to the box

and wipe the worms off into a dish of tap water:

The worms are swirled around and allowed to settle, the water poured

off, and new water added, and rinsed this way several times while I'm

also thawing the frozen food and preparing the brine shrimp and

microworms. By the time I'm done they are much cleaner and ready

to be dropped into the tank from my miniature baster. The box of

worms gets a few fresh pellets of cat kibble. I started with

Science Diet

feline

maintainance light, since that's what I fed to the cat, but I have

recently learned that kitten food may be better because it has more

vitamin C that will eventually get passed through to the fish.

However, the Science Diet kitten food molded too easily, and the worms

did not seem to swarm over it as readily, so I have switched to Purina Kitten Chow, which seems to work a little better.

Here is the fed culture ready to be covered, wrapped, and put away:

Alternative foods for grindals include trout chow, other

fish food, baby cereal, or soaked slices of bread: they're really

not very picky. But the kibble is clean, easy to use, keeps them

up on the surface for easy harvest, and resists mold better than baby

cereal.

All my fish love grindals, and I love getting a couple of tablespoons

of live

food daily from a bit of cat

food and a

small investment in

space.

And I have not had to restart the cultures very often--they've gone

about a year between restarts; if I add too much food and

some molds (rare but it does happen), I remove the moldy bit and the

culture goes on; if it gets

a little too wet, a few days with the bag loosened dries it out a bit;

if

I leave on vacation I just let them go in their bags until I get back

(refrigeration was a bad idea: the worms died and it was

nasty).

I recently discovered what seems to be a really good way to start new

cultures: I take the cleaned, rinsed worms when I have some

extra, pull them up in the baster, and let them sit in the baster until

they sink into a sludge about to fall out of the tip. I put a few

drops of this concentrated mass of worms over a fresh piece of kibble

in a new container of fresh, damp, worm bedding. There is a good

ratio of worm to food right away, so the culture starts without a lot

of moldy kibble or hungry worms trying to find their way to the new

food.

Plastic shoeboxes are also popular to keep grindals, but beware that

loose-fitting lids

invite fruit flies. Another unwelcome visitor to grindal

and white worm cultures are springtails, tiny little bugs that look

like little white specks on the surface of the culture media.

When they invaded my white worms (possibly coming from a bag of

poor-quality peat I used for the bedding mix), they quickly took it

over, despite attempts to flood and freeze the culture to kill them off

(but spare the worms). With the grindals, I found that they

seemed to outcompete the springtails, without any special

treatment. I saw a few springtails, then a few more, then they

gradually disappeared over a few weeks.

Grindals on scrubber pads

After an outbreak of mites in my grindals, which recurred after I

subcultured them very carefully trying to avoid carrying along any

worms, I tried some "soiless" cultures on green scrubber pads.

These are now going great guns and the mites have not entirely

vanished, but are remaining at a low, manageable level. I also

switched from using plastic bags to an old pillow case to seal out the

fruit flies, which also is working quite well. These

cultures are much slower to get established, and respond to

overfeeding with impressively nasty molds if you're too

enthusiastic--daily feedings are best, just enough for the worms to eat

within 24 hours.

Here is the stack o'cultures in the pillowcase:

And what it looks like inside:

Baring the worms:

And this is what the culture looks about 8 hours after feeding:

And the worms on the lid are ready for harvesting with a swipe of the finger:

The goop at the bottom may be where there are freshly hatched worms, so maybe it shouldn't be thrown out:

And you can make a little more of that by periodically rinsing the culture pad with a little tap water (not dechlorinated).

This is the dense, well-established culture:

And this is a new culture, only about 2-3 weeks old, given new blobs of

worms and dampened kibble, little by little, only feeding as much as it

will eat overnight. It takes many weeks to build up to a

well-established culture like the one above.

I have not been raising them on the pads for that long--about 18

months now--and don't have clear criteria for splitting or renewing

cultures. Gradually increasing the number of kibbles fed

daily--again, only as much as the worms will eat--is a very slow but

safe way to get them to the size and productivity of the very well

established culture shown above.

I think I got much

faster establishment recently by a different technique, and I will try

this again in the future. The cultures are generally 3-5 pads

thick, and when my best-established culture got overwatered, and

started to smell of decaying worms, I removed a couple of the middle

pads, rinsed them under the tap (gently, trying to remove some of the

foul smelling muck but not let all the enmeshed worms escape), and

switched it out with a clean pad from the just-started cultures.

All three cultures did well after this.

Overwatering is a

problem with these cultures, as is drying out on hot dry days. I

generally add a little water to the bottom of the cultures daily after

I harvest and feed them--just enough to keep the bottom quite wet and

have a little water that will puddle if I tip the culture on end a bit,

but not enough to immerse the entire bottom of the culture box in

water. If they do get overwatered and a little moldy, pour

out some of the excess from the bottom of the box. Feed very

sparingly, and give them time to come back. They have come back amazingly well if I give them time.

White

Worms

I gave up on these because my apartment was too warm for them

(temps easily to 80 degrees in the summer even under the sink),

and I could keep them going but never really thriving, whether I used

synthetic sponges or dirt with ice packs in a cooler (and then I

discovered grindals, which do thrive here). Many people who keep

them have cool basements or use a refrigerator or wine cooler set to

about 55 degrees F. Another alternative I just learned about from

Jack Heller is to cut off the lower half of a 2 liter plastic soda

bottle, fill it with water, and freeze it. That block of ice, if

placed in a standard styrofoam fish box, in the middle of a few inches

of worm bedding, will take 2 days to thaw, at which point it can be

replaced with a freshly frozen block of ice. It gets too cold

right next to the ice for the worms, so they hang out a few inches away

from the ice block. They're otherwise cultivated just like

grindals, although some people grow these up on a much larger

scale. Some images of Charles' Harrison's white worms are here.

They are reputed to be fattening, so are not recommended

as a daily dietary staple.

Daphnia

I keep a few going in a set of open trays on a

windowsill--in shallow water, figuring that without filtration or

aeration, my carrying capacity is limited by surface area. I

used to just toss them a pinch of dried brewers' yeast or a bit

of baby food sweet potatoes every few days, and change their water

with aged tank water when I do tank water changes. I did not get

many daphnia out of this--just a few dozen here and there as a treat

for favorite fish. But it kept them going until I saw the

light: during Joe

Fleckenstein's talk on live foods at the 2005 MASI show, he said he

used a little bit of everything he'd heard people used to feed them,

including, most intriguingly to me,

paprika. So I went out and got several things he mentioned--soy

flour, spirulina powder, and yeast from the health food store, a big

jar of paprika from the international grocery, and (my own inspiration,

no blame to Joe) some freeze-dried

peas, also from the health food store. I put all that you see

here together--thats 180g or about 6 oz of spirulina powder, 1 pound of

paprika, a 3.5 ounce container of the peas, about 4 ounces of soy

powder and about 4 ounces of brewer's yeast. Again, the

proportions were simply what I bought of each one, and not specifically

Joe's recipe. I bought a big jar of paprika, so there is a lot of

pepper in my version.

I whirled these together in the food processor (with a towel wrapped

around it to keep from pepper-spraying myself) until the peas were

powdered and all well-mixed. I put it in a spice jar and sprinkle

a bit on the daphnia daily. I have seen an incredible increase in

daphnia yield under this new regimen--so many that I suspect one of my

trays actually crashed from overpopulation because I wasn't harvesting

them fast enough.

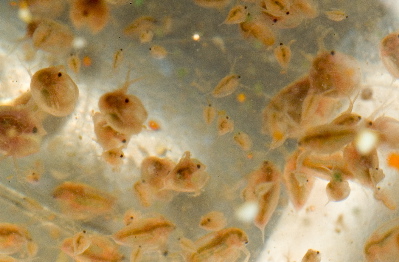

Here are happy daphnia in their trays on the windowsill:

I keep them on the windowsill because it's a handy surface; they have

also done ok in a closed closet for a time. Light is not

necessary. The culture gets mucky on the bottom, but that's ok as

long as it doesn't get stinky.

I use a baster to harvest them. You can see how they cluster in

the corners of the tray above. I put the baster there to avoid

the mulm from the bottom of the tray:

And I replace the liquid I remove with water from the tanks, because

they're supposed to prefer to live in aged tank water. I never

give them freshly dechlorinated tap water, only water from my

tanks. They seem to flourish a little more in the water from my

"hard water tanks" which is St. Louis tap water supplemented with a bit

of SeaChem LiveBearer Salt. I top them up at least once a week

with tank water, and

when the culture starts to stink, once every few weeks to a month, I

drain the entire culture into a brine shrimp

net,

along with whatever goop is on the bottom of the box, and rinse it back

into the box with tank water--in effect, doing a 100% water change, but

with aged tank water. I think I have daphnia pulex, which are all

caught by the net, but Moina macrocopa (often incorrectly called

Daphnia moina) are preferred by many fishkeepers

because the newly hatched babies are smaller than baby brine

shrimp--great for small fry--but require different feeding techniques

because they will slip through a standard commercial brine shrimp

net.

.

.

The fish are quite pleased by every feeding of daphnia.

Although in theory they could survive in the tanks for days, they

never last very long before the fish chase down every last one of them.

One neat idea for making the best use of daphnia comes from Jack

Heller, who calls them excellent "babysitters" for young fry. If

you have to be out of town for a few days, putting some daphnia in the

fry tanks helps keep the water cleaner, as the daphnia filter feed on

some of the tank waste, and they also will produce babies that the fry

can eat (assuming the fry are too small to eat the adult

daphnia). Add a couple of ramshorn snails and your babysitting

crew is complete--they will help produce infusoria from the fish waste

that the daphnia will eat.

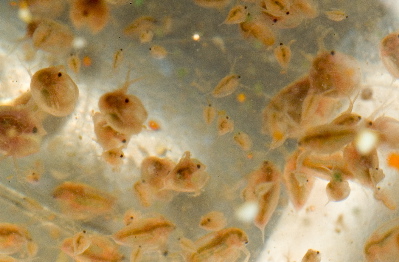

Daphnia vs Moina

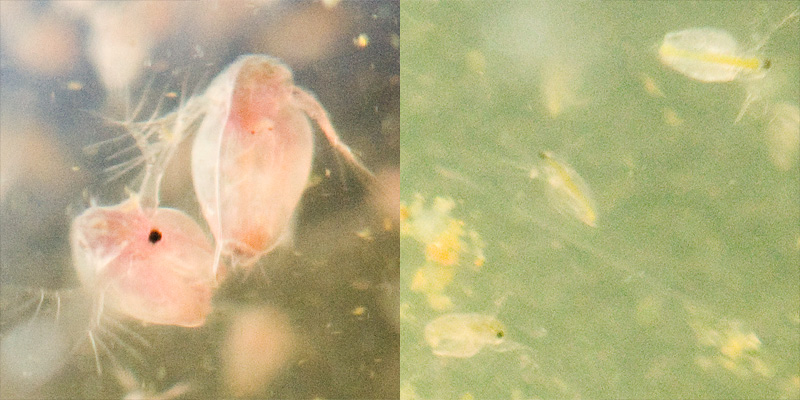

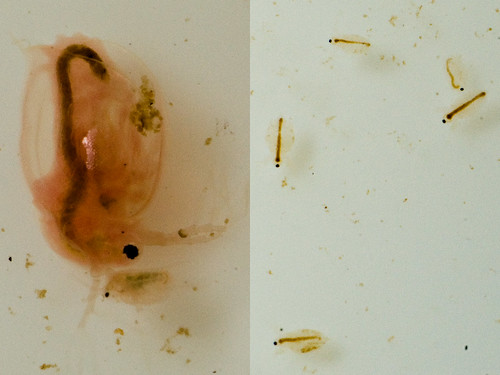

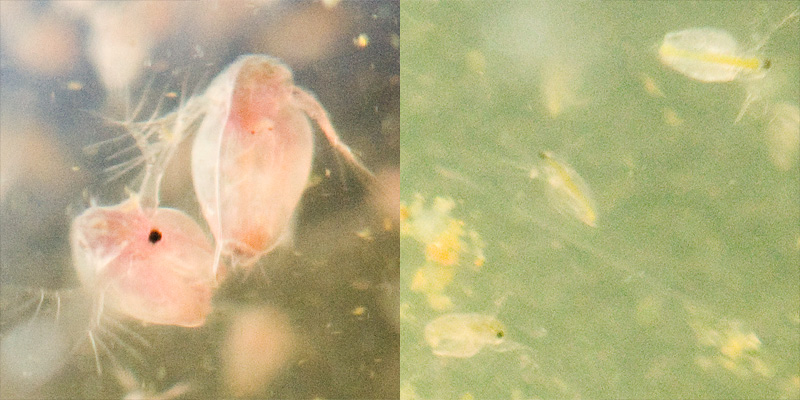

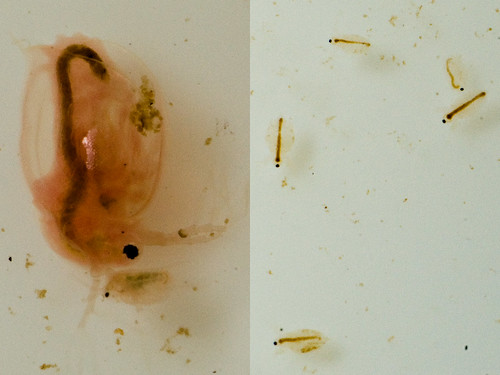

Adult Moina, a similar animal from a different genus than Daphnia, are

the size of juvenile Daphnia, and juvenile Moina are smaller than newly

hatched brine shrimp. I recently got another starter culture of

Moina because the very small juveniles should be excellent for fry.

They're so small that they don't have enough density of pigment

in their bodies to appear orange to the naked eye, as the Daphnia do,

and they're about the same size as the cyclops that sometimes

contaminate and can take over neglected Daphnia cultures. But

though the both critters pretty much look just like white dots to my

eyes, Moina swim like Daphnia--jerky short

almost random-walk movements--and the cyclops are supposed to swim in a

smoother steadier motion. A closer look at the cultures (the

best resolution I can get until I find my macro extension ring for the

camera) reveals that the Moina do look just like juvenile Daphnia, and

up close, they have an orange cast just like the Daphnia.

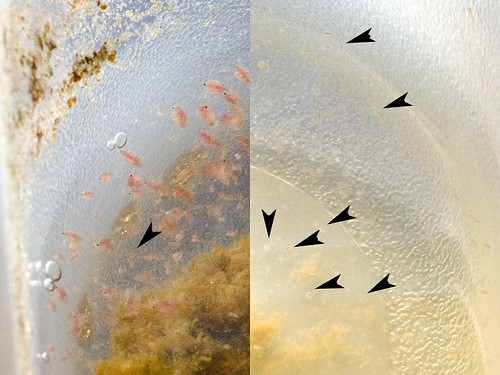

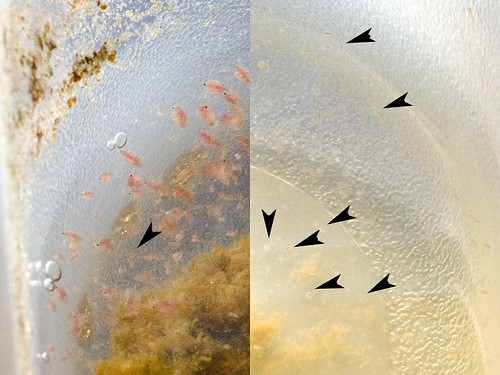

Here are the cultures shot side by side (identical scale: the adult Daphnia are about 2mm long).

The arrowheads point to Moina in the right image--hard to see, of course, but easier to make out if you view the image larger here, and to a similar appearing juvenile Daphnia on the left image.

Here they are in more detail, at the same scale for both the larger images and the inset closeups:

Confused

flour beetles

I keep a few of these in a covered drum bowl in my closet with some

whole wheat flour. They're covered because I don't want them to

make their way to my kitchen and start eating my wheat and flour.

It is not easy to separate the beetles from the flour, so they mostly

sit quietly and unbothered by me in the

closet. Occasionally I grab a strainer and sift a few out

to sprinkle into the tanks, where the fish enjoy the treat. They

need whole wheat flour--white flour doesn't have enough nutrients to

keep them going in any dense, useful quantity. Once I thought I

could cleverly recycle some stale gingerbread cookies made with whole

wheat flour as crumbs for the beetles, but the spices didn't agree with

them and the large crumbs made it harder to separate out the

beetles. That was dumb. They get straight whole

wheat flour only now.

These beetles are well armored, and are best suited as food for larger

top feeding fish. If you dig a little deeper in the flour you can

harvest a mix of larvae and beetles, and the larvae are more appealing

to many fish.

They're called confused because they were confusing to taxonomists

trying to classify their species many years ago, but the beetles are

quite clear about eating and breeding and otherwise doing their thing.

Endler's

livebearer fry

Since I have a few of these fish in most of my tanks, there are nearly

always a few fry available to supplement the diet of the other fish, if

they're hungry enough to chase them down. They're live food

by default, not really by design. This also has the pleasant side

effect of keeping the Endler population under control; they're not

known as "Endless livebearers" for nothing.

Red

Wigglers (earthworms)

I keep a bin of redworms to compost my kitchen scraps.

Occasionally the fish get a treat of some fresh chopped worms.

Recently I tested a rolling vegetable mincer vs my regular cleaver to

see which most efficiently chopped the worms, and the cleaver won hands

down because the mincer was too dull and didn't cut cleanly through the

worms. For just a few worms at a time for my largest fish

(smallish throrichthys cichlids), I just rinse them and pinch them off

between my fingers into 1-inch chunks.

I learned most of what I know about vermiculture from Worms eat my garbage, which is

available here,

and from the forums at HappyDRanch,

from whom I ordered my Can O' Worms. I use Magic Worm Bedding

here too with good success. The bin sits in the kitchen and

doesn't stink.

Snails

My planted tanks produce an abundance of snails, mostly ramshorns, and

when I was keeping goldfish, I’d toss the excess in their tanks,

and

they rarely hit the bottom of the tank before being snapped up.

Loaches also love them (although my present dwarf Sidthimunki loaches

don’t seem to eat them), and so did my adult Thorichthys

cichlids. Many fish that are too small to take on whole snails

will be delighted if you crush the snail shell and toss it back in the

tank.

More

Web Resources

Some good web resources for more information on culturing live foods:

In case you missed the first link, this is where you can get Mike Hellweg's book Culturing Live Foods

The Bug Farm website

discusses which foods for which fish as well as culture techniques

The

American Killifish Association Beginner's guide has a good section

on live foods

The Krib

discusses an extensive variety of live foods

The Live-Foods list is not very active but seems to be pretty good

The Killietalk archives

include many good threads on live foods

Notes from Jack Heller on

live food cultures, including paramecia.

Some images of Charles'

Harrison's live food cultures

Magic Worm Bedding

is available by telephone or mail order directly from the company, but

not yet available directly online.

And, of course, your local fish club is usually a great source of

starter cultures and helpful people who know enough to generate excess

cultures to give you a start.

Return to My Fishroom

Back to Fish Page

Return to Diane's Home Page

http://debunix.net/fish/CharlesLiveFoodCulture.html#CharlesShrimpHatchery

http://debunix.net/fish/CharlesLiveFoodCulture.html#CharlesShrimpHatchery

.

.